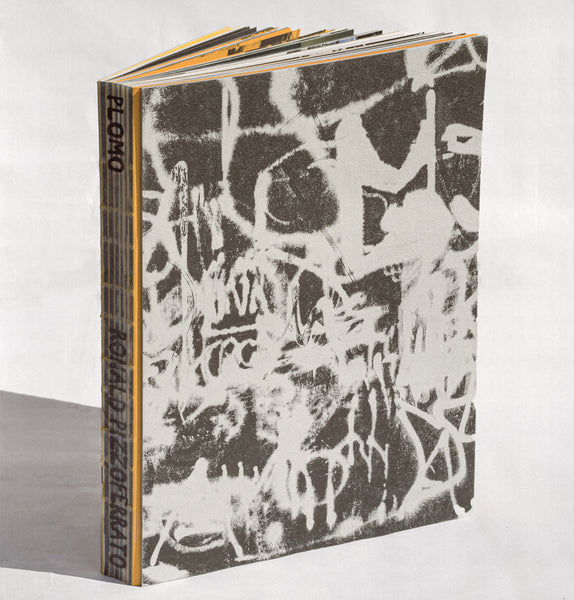

Ronald Pizzoferrato

Plomo - SOLD OUT!

Artphilein Editions, Lugano — 2021

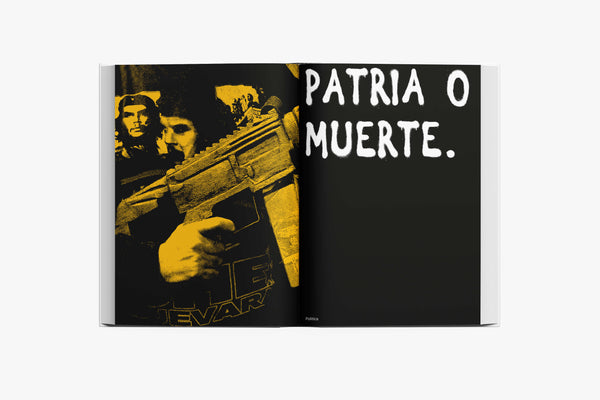

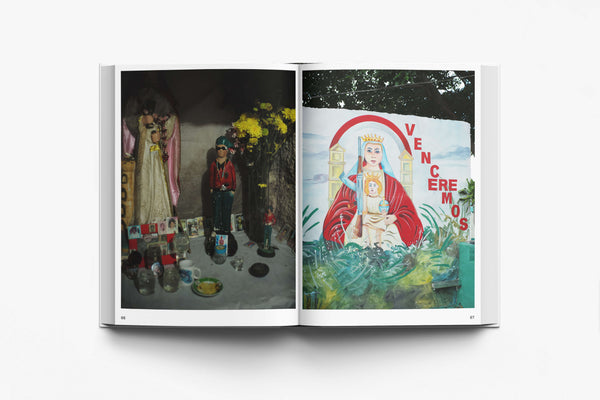

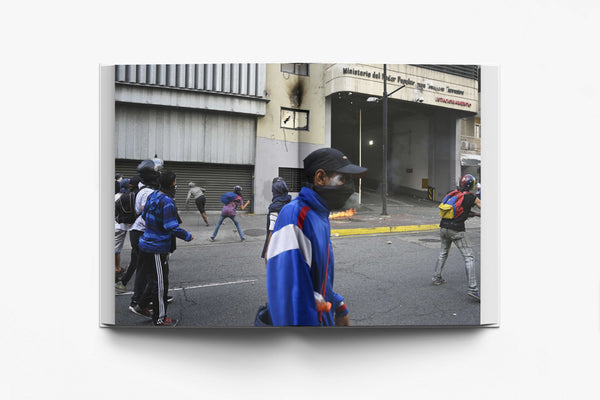

Ronald Pizzoferrato’s work does not seek to judge those who commit violence, nor to romanticize them. It invites us to think that violence is part of the overall structure of our society, and it has manifestations in every area of it. This violence is part of the history of Venezuela and it is embedded within the way power and justice are exercised, formally or informally, on a daily basis, on all levels of society, from the “highest” to the “lowest” points of symbolic status.

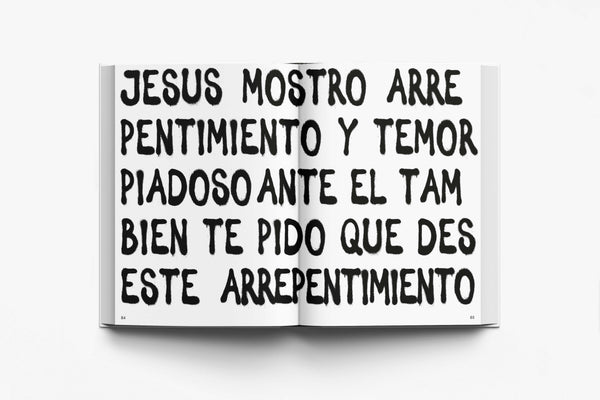

PLOMO presents an exploration of the phenomenon of excessive violence in Caracas; it focuses on the value of the creative actions of people whose lives are determined by violence. Many academic works that aim to understand and “dialogue” with the phenomenon of violence in our country only result in an explanation of our social problems as a lack of personal capacity to adapt to external models, almost always European ones. These figures of authority usually declare that we live in violence either because we are too wild to adjust to the capitalist system—and its supposed notion of honest work—or because we are too immoral to maintain the high values that Socialism demands. Our social reality, although affected by external forces, corresponds to its own internal logic. Any research work that sets out to understand this particularity has to begin by not allowing our reality to continue to be told through other people’s stories. Stories that almost always denigrate us, put us down in relation to some imposed scale of values, and do little to help us better understand our world.

PLOMO is part of a large network of actions undertaken by the author and his collaborators, which range from graffiti, art, research, and cultural criticism, all with the mission of the decolonization of the Caribbean cultural front.

PLOMO is an anthropological work under a semiotic lens, which is to say, an exploration of the ways of being human, taking into account the invisible power structures that connect all things, and how those forces become evident in our expressions and culture.

(Excerpts from Alexander Chaparro's essay)