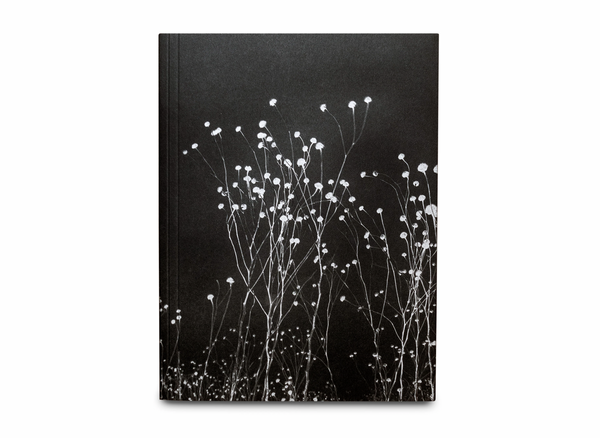

Léonard Pongo

The Uncanny

Gost Books, London — 2023

The Uncanny by Belgian-Congolese photographer Léonard Pongo is a visual interpretation of his experiences in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Following friends and family in the country, Pongo became immersed in their vision. He let them decide what he should witness as he attempted to understand the place, reconnect with his heritage and reconcile his preconceptions with realities.

In 2011, Pongo travelled to the Democratic Republic of Congo to photograph the country’s general election and its impact on society. He soon became aware of his inability to define which stories mattered, and to faithfully report on the overwhelming experience he went through. As his awareness of this increased, he came to terms with the limits of photography to show ‘the truth’ as well as his own limitations in accessing and analysing the environment, bias, and stereotypes. The project evolved into the photographs which form his first book The Uncanny.

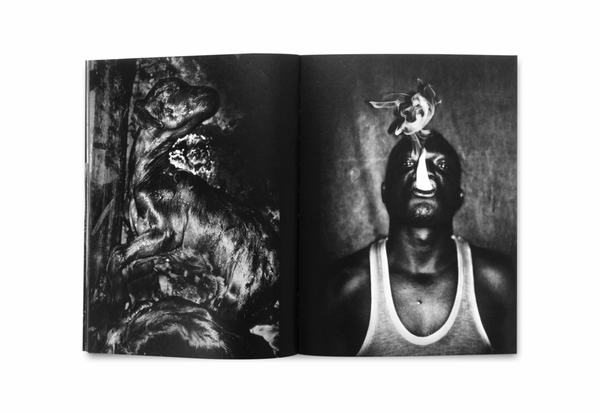

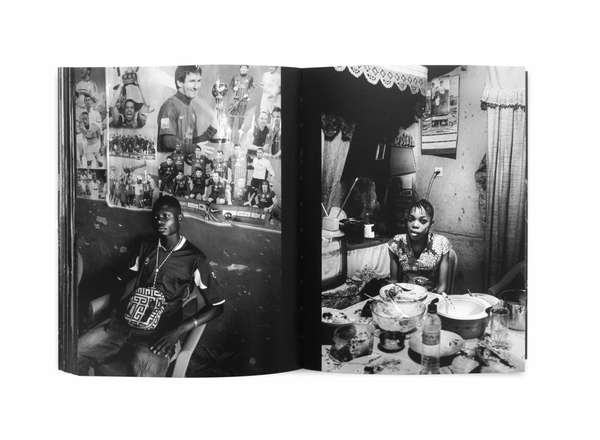

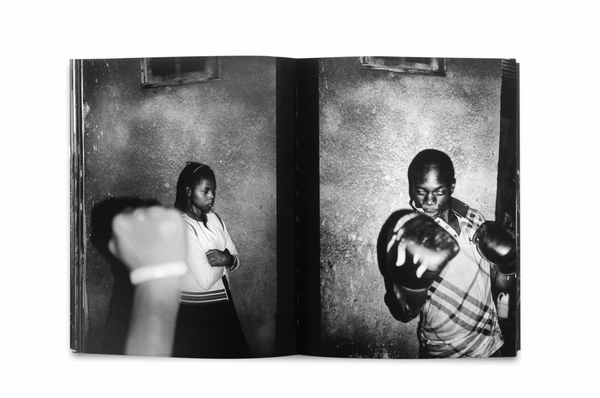

The black and white photographs in the book show an often dream-like and abstract journey through landscapes, domestic interiors, streets, dance halls and churches. Disorientating perspectives and use of long exposures give the impression of movement and figures disappearing out of the frame. A lack of formal narrative lends a feeling of instability and occasional threat. Portraits of both strangers and friends show those aware and accepting of Pongo’s presence—some disregarding the camera and others requesting its presence. Devoid of colour, night and day are hard to differentiate in this vision in which the religious, spiritual and the secular are intertwined with the uncanny. Rather than documenting a country, Pongo has attempted to document his personal experience of the country, translating the vibrant, overwhelming and ungraspable into pictures.

‘No image has a title. We dispense with the reference and with any possible language (French, Lingala, English) that might be called upon because there are no routes, no passages. There are no itineraries to be followed that would indicate what to see, and where to look. Wrong questions collapse—questions trying to unmask the origin (Where do you come from?), impose authority (Who the hell are you to...?), or hammer in the nail of guilt (You shouldn’t have...you shouldn’t...look). Because the pictures stubbornly refuse to show. They are not about identity politics, distributing places, or fixing the lines that the eye must follow. The question which seems unavoidable is therefore undermined—that of the point of view’. Nadia Yala Kisukidi