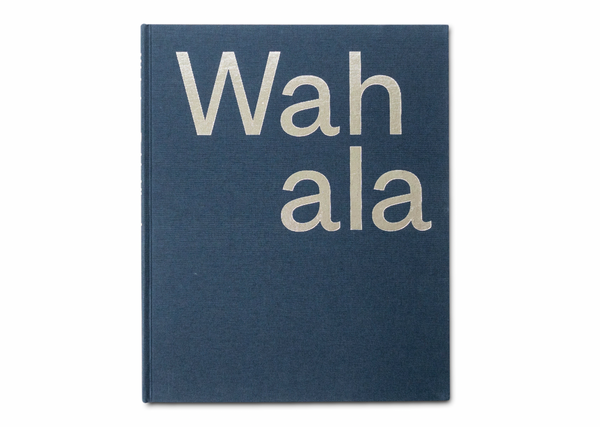

Robin Hinsch

Wahala

Gost Books, London — 2022

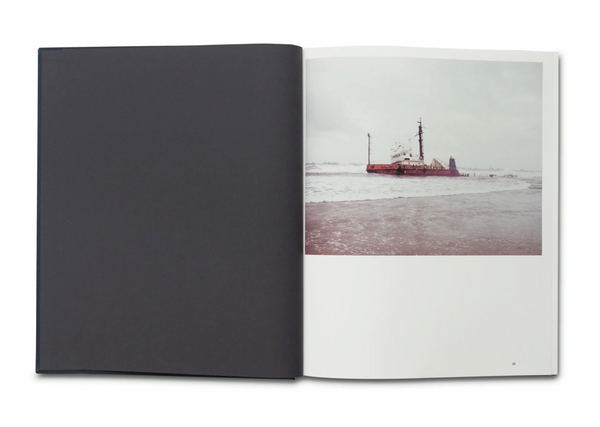

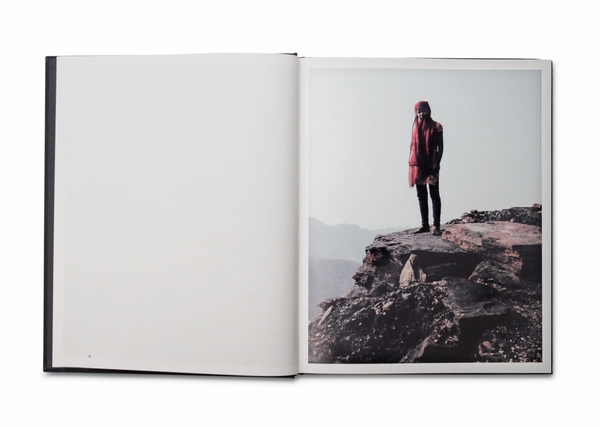

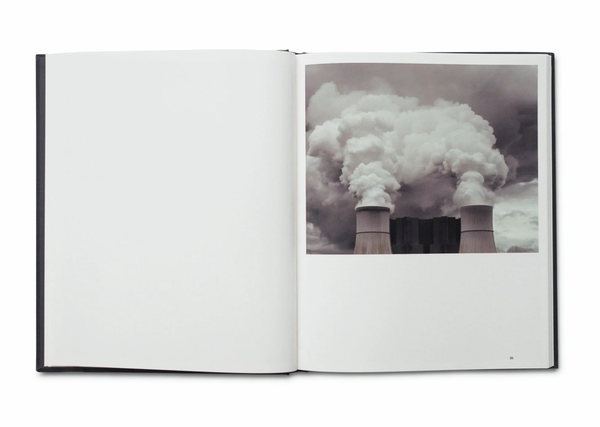

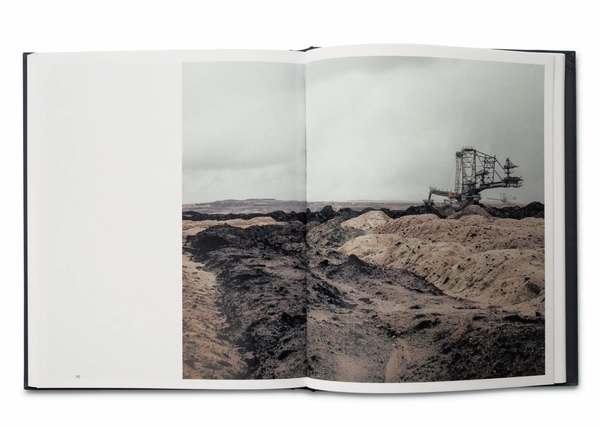

The images in Wahala depict both the places in the world where raw materials are extracted from the earth for profit, and the people who make their homes there. Photographer Robin Hinsch travelled to where the human impact on the planet was particularly visible to confront the viewer with the blunt ecological and human repercussions of the global reliance on fossil fuels.

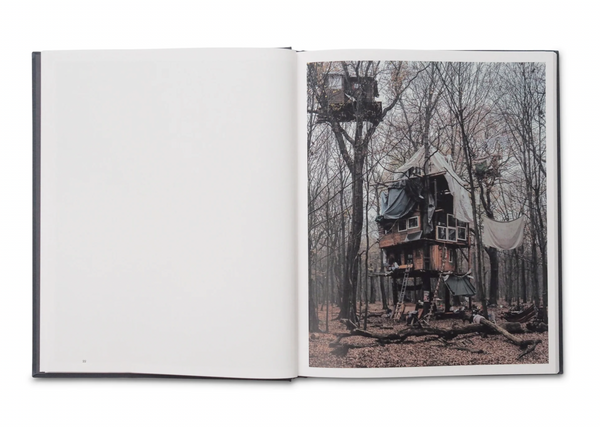

The photographs in the book were made in the oil fields of the Niger Delta, Nigeria; the coal belt of Jharkhand, India; and the open cast mines of Brandenburg and North Rhine- Westphalia in Germany and Silesia in Poland. They shift between details and overviews, landscapes and portraits, the familiar and the foreign, disorientating the viewer as to what and where they are looking at. The images are cinematic—dark and brooding skies, dramatic landscapes lit by gas flares, collapsing ruins of buildings. Deviating from straight documentary, the book constructs new narratives of associative imagery to tell the story of exploitation—both by international companies and by those living in the areas impacted by their presence, in turn, hacking into the system.

''Wahala' translates the violence of these global mechanisms of fossil fuel extraction into visibilities that help us grasp their complexity… Now we can understand: with the exploitation of the planet we destroy ourselves' - Dr. Sophie Charlotte Opitz

The Yoruba word 'wahala' means 'problem' or 'stress' and is a widely understood pidgin term in Nigeria. It rarely stands alone, but when it does it implies there is a problem that leaves one shaken or speechless. Hinsch’s focus on where man’s ecological effect on the world is most glaring aims to have this impact—showing both the subject’s complexity and that the problem is our problem.

‘Fossil fuel infrastructures are manifold and extend well into our immediate environment. From wellheads, oil pipelines, coal mines, tunnels and elevators, these channels of fire fork, branch out and merge back into large bunkering facilities, refineries, power plants, and filling stations. Finally, they reach the tanks of our cars, the smaller gas pipelines of our houses, the electricity with which we charge our phones. In fact, the massive activity of burning fossil fuels sticks, in one way or another, to anything we buy in the supermarket. Next to nothing would make it to the shelves without the fuel burnt in trucks, containerships and airplanes. Oil and coal are fueling a gigantic choreography of commodities and people, moving around the earth on an ever-greater scale and with ever more speed. Fossil fuels thus stick to our lives like a fine coating only visible in black light, a thin, invisible layer, viscous and almost impossible to wash off.' - Moritz Frischkorn

To make this project, Hinsch collaborated with Pinaki Roy, a teacher and social activist working at the Jharia coalfield in India; Fyneface Dumnamene, an environmental justice activist, human rights defender and the executive director of Youths and Environmental Advocacy Centre (YEAC), Nigeria; and Nnenna Obibuaku a freelance journalist and multimedia professional working throughout the African continent.